A Tasting Menu: Food and Race in 18th and 19th-Century Caribbean Paintings

This tasting menu is a proposal for future dinner parties for anyone interested in the intersection of art, food, and the politics of representation. I focus on 18th and 19th-century Caribbean paintings by Agostino Brunias and Marius-Pierre Le Masurier. These two painters contributed to the natural history discourse and social and racial classification visualization. The dishes I created are meant to be my artistic interpretation of my analysis of the paintings. In addition to the dishes, I will also create my artwork to reflect my analysis.

Initially, my idea was to use art to evaluate how people of color viewed each other. However, I could not locate any painters of color in the Caribbean during the 18th and 19th centuries. Therefore I am evaluating how a European, or a person of European descent, interrupts how people of color interact with each other. There will always be something lost in the initial painting as the Europen will not capture or understand specific details that are interchanged between the individuals, but also the painter is injecting their thoughts and opinions into the piece. Is the painter creating an idyllic landscape compared to the cartoonish representation of people with dark skin, while those with lighter skin may have more European features?

What caused me to be interested in this topic of the inter-racism between people of color and whether or not it is depicted in artwork was the fact that I didn’t realize I had experienced racism until it was from another woman or a group of women of color. This boggles my mind why people of color are willing to put one another down even though, as a collective group, we all want the same thing, to be treated equally, with respect, and without prejudice. Did they realize that they were being racist or have passive-aggressive ways of differentiation just been ingrained in our culture and psyche?

I started to examine paintings by the 18th Century Caribbean painters Agostino Brunias and Marius-Pierre Le Masurier. I enjoyed evaluating their work and wanted to take it one step further, and a creative way to do so was to create a tasting menu inspired by the interactions between people of color within the paintings and the food depicted. Creating a tasting menu based on these paintings was tedious, and I didn’t know where to start. Therefore, I began by creating my artwork that would reflect the paintings I selected to help inspire the menu.

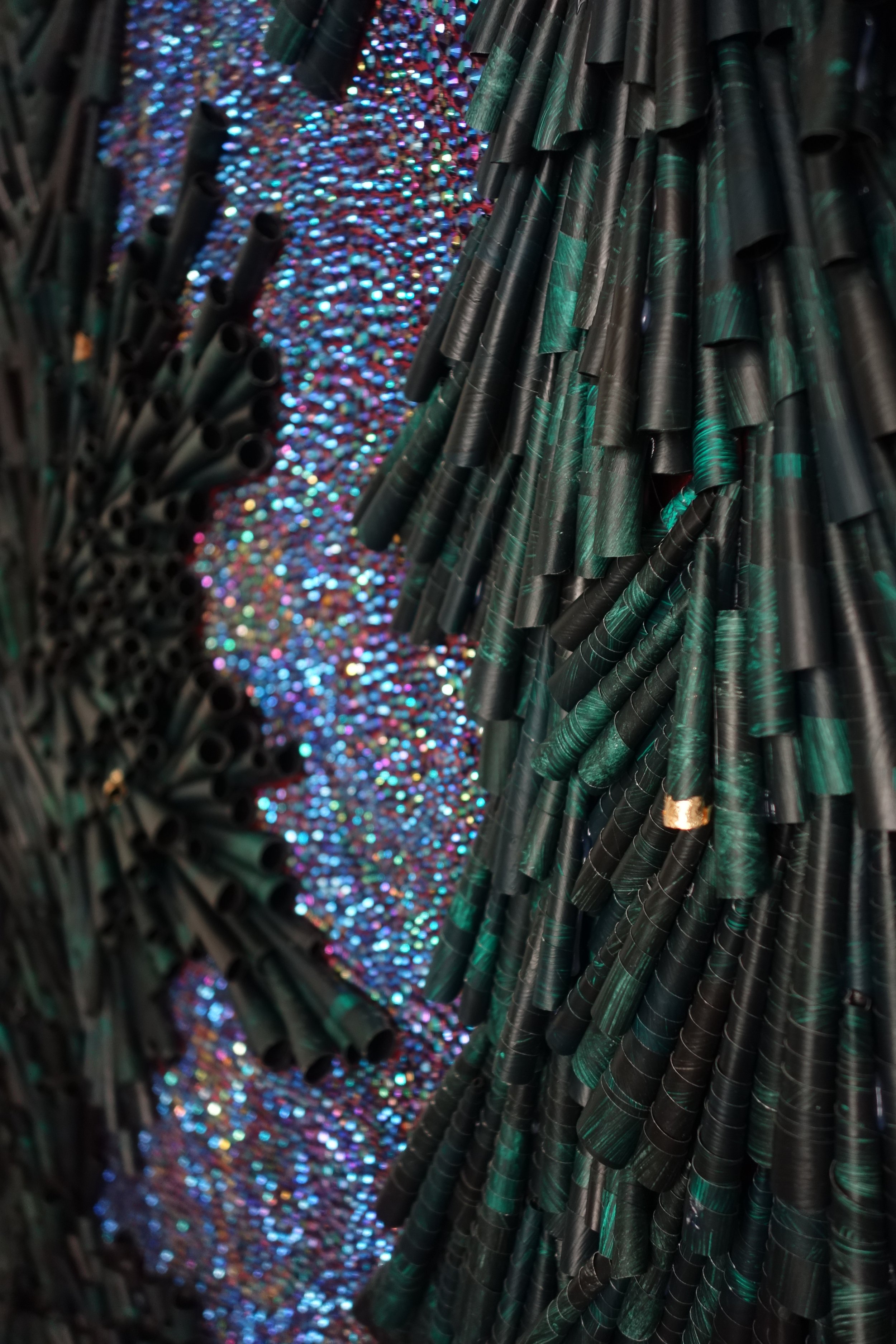

My painting comprises paper, paint, glue, and a canvas. The first step was to paint on canvas. I chose metallic copper paint that I mixed with cranberry red. Then I took large sheets of paper and painted one side black while the other side was painted using a mixture of black paint and Phthalo Green. I chose these colors as Agostino Brunias and Marius-Pierre Le Masurier have a muted color palette but then have elements that pop with copper red, bright blues, and yellows. After the sheets of paper had been painted and the paint dried, I cut them into strips of all different lengths. Then came the arduous yet meditative task of rolling the strips of paper into a cone shape. Some days I spent 7 hours just rolling or "quilling" the paper. When I reached the end of a strip of paper, I would cut the edge into a semi-circle and then glue the edge down to the cone.

Repeat this process many times over. While rolling the paper, my mind would wonder what dish I could create using this process, how the artists might have felt during the painting process, or how they felt depicting a group of marginalized people. Did these painters select this population because they wanted to elevate how the world viewed them? Was it solely for documentation purposes? Who commissioned the paintings and why? Why is painting a group of people who are a mixture of European and African descent important? What is their role in society? What jobs or professions did they have? What does the environment in which they are depicted say about the group of people? How does the painting style of these artists enhance or take away from the value of those being depicted? What is Caribbean Impressionism? What did those depicted eat?

So many questions kept coming to mind while creating my work inspired by these artists.

The best place to start was to define what Caribbean Impressionism is. Curators at the Brooklyn Museum in New York define it as an exchange between Europe and the Caribbean in the eighteenth century that was inspired by Paul Cézanne, Winslow Homer, Claude Monet, and Camille Pissarro, (https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/touring/francisco_oller). As someone who studied Studio Art and Art History during my undergraduate studies, I was amazed to learn that Impressionism had made its way to the Caribbean. Why, for the most part, are all of our studies European centered? Why are Europeans the ones to write or depict the history of a place? Did these painters inflict their European views on those they painted? How are people of color, regarding the class, represented compared to those who are white? Did their skin color dictate what foods they could purchase at the market?

The artwork that I am creating ties into this through the interpretation of creating something that is elevated out of materials that are used every day. It straddles the line of is it art just as the idea that a person who was categorized as mulatto was higher in class than an enslaved person but was still looked down upon by someone who was white. The color story also ties my work to the artists that I have decided to focus on. The shapes that are formed by the grouping of paper are also in an impressionist style, in my opinion.

While creating the recipes for the dishes, it was frustrating as I started with sugar. My base was a family tart recipe that consisted of a basic dough recipe using Crisco and either guava paste or stew coconut. The recipe was my great-grandmother's, and everything is measured in handfuls. I small handful of sugar, a heaping handful of flour, and add flavorings such as vanilla or almond extract to taste. This is difficult for me to interpret as we all have different size hands. I never met my great-grandmother, so I did not get to see her method of making it, and my grandmother only makes it on special occasions such as Christmas. My grandmother, the youngest of seven, is the only one of her siblings who know how to make it; therefore, there has never been an exchange of ideas on how to improve the tart between family members. Who can make it the best? Maybe the recipe my grandmother provided me has already been altered as she may have found ingredients in New York that are not available on Anegada, a small island in the British Virgin Islands. While sourcing the ingredients for the dish, I was brought back to a reading from High on the Hog as well as an episode of Taste the Nation with Padma Lakshmi, who speaks with Michael W. Twitty, author of The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South, about how enslaved people created dishes and remembered recipes. -There were no written recipes, and they had to use their past knowledge, senses, and memories to create dishes. Such as the pound of grain and the rhythm it created to know when it was done or how much longer it needed to grounded for.

Figure 2: Marius-Pierre Le Masurier (French, active 1769-75). Marché à Saint Pierre de la Martinique, 1775. Oil on canvas; 162 x 227.5 cm (63.7 x 89.5 in). Avignon: Musée Calvet, 23.623.

Figure 1: Agostino Brunias (after) (Italian, c.1730-96). The Barbados Mulatto Girl, 1779. Print. Bridgetown: Barbados Museum & Historical Society.

The Menu

-

Fruit

This dish is based on Agostino Brunias (Italian, c.1730-96). The Barbados Mulatto Girl, 1779. Print. It is an Acerola cherry jelly surrounded by stewed and pickled Granny Smith apples. There is also cinnamon, mint, and thyme. In the painting, the Mulatto woman appears to be purchasing some fruit from the two other women. Due to the vagueness of the fruit and the research I could find on this painting, I decided that it had to be either an Acerola cherry or an apple.

In addition, how Brunias painted the hand of the Mulatto woman reminded me of Michelangelo's hands of God and Adam in the 16th chapel. Was Brunias implying that the Mulatto woman is providing "life" in the form of a livelihood by purchasing fruit from other individuals? If it is an apple, does that further the religious implications and the idea that this fair-skinned woman is giving or providing a life for the other two?

I wanted the first dish not to be too sweet, more acidic, and tart than anything else. I also wanted it to appear vague in appearance as the eater does not know for certain what they are about to eat. I created an Acerola cherry jelly that was surrounded by pickled apples as well as stewed apples. Cinnamon, honey, and jaggery sugar were used to sweeten the stewed apples, while the pickled apples had star anise and green peppercorn. In the very center of the jelly, I placed a sphere of apple juice on top, which then made the dish appear breast like, which furthers the implication of providing life, as a mother’s breastmilk provides life to her children.

I also paired this dish with a cocktail composed of Sour Acerola cherry juice, Velvet Falernum, White Rum, Simple Syrup, and Orange Bitters.

-

Fish

The next dish in the tasting menu focuses on fish from Marius-Pierre Le Masurier (French, active 1769-75). Marché à Saint Pierre de la Martinique, 1775. Here Masurier paints many different interactions between people of different ethnicities and social spheres. It is essential to understand and analyze the politics of representation that can be found in these paintings. Many scholars believe that artists such as Brunias and Masurier were painting Mulatress as, during this period, a new race was being created by mixing European and African ethnicities.

When I created this dish, I wanted there to be a mixing of unexpected flavors. In Masurier's painting, he depicts many different species of fish and various products available at the market.

This dish was the hardest to conceptualize as I had various ideas of what to create. At first, I thought about cooking a piece of fish and then by using artichoke hearts, create scale-like shapes to mimic the shell of a turtle and have that be surrounded by a banana or plantain broth with pickled habanero peppers.

The second idea was to create a play on surf and turf by using mussels and some kind of poultry. The poultry would have been presented inside of the mussel shell and then the mussels would have been used to create a sauce.

However, I decided to incorporate snapper, stewed and then fried leeks, pickled habanero peppers, purple and red potatoes that had been sliced thinly, and then fried, lime segments plus some of its juice, and black lava sea salt to finish the dish.

The cocktail paired with this dish comprised of Dark Rum, Yuzu Liquor, Ginger Ale, and Agave.

-

Sugar

The last dish on the tasting menu focused on sugarcane, also from Marius-Pierre Le Masurier (French, active 1769-75). Marché à Saint Pierre de la Martinique, 1775. I focused on the bottom right-hand corner of the painting, where a Mulatress and a white man engage flirtatiously with one another as he has his hand on his shoulder. She also holds a piece of sugar cane, and how her scarf drapes around her shoulder, creating a heart-like shape. Are these elements meant to represent the sweetness of temptation or the living in the moment? Sexual relations between white men and black women had been an integral part of the exploitation of slaves wherever slavery was established, and its effect on relations between the races was and remains fundamental. For many young European men coming as soldiers or sailors, government officials or workers on plantations, the Caribbean was a liberation from the limiting sexual conventions of European life, and when I created the final dish, I wanted to be free of baking and flavor constraints.

There has been a connection between sex and sugar, such as the sweet connote of affection. Sugar is also often associated with women, sweet in both literal and figurative senses. Furthermore, sugar is used to describe the voluptuous figure of the mixed-race mulatto, often associated with seduction and immortality. Different sugar categories have been used to define women of different skin tones (https://slideplayer.com/slide/5064185/).

When I created this dish, I was drawn to a family recipe of guava tart due to the sweetness it contains. I wanted to intensify its sweetness, so I used different types of sugar in it, such as jaggery, muscovado, white, light brown, and turbinado.

It is a three-layered tart with guava at the bottom, stew coconut with cinnamon, ginger, and dark rum, and then a final layer of mango, pineapple, and passion fruit preserves with thyme, star anise, and pineapple spice rum. Each layer had a different type of sugar that I used while constructing its flavor profiles.

The dough was made with jaggery and muscovado sugar instead of white to try and mimic the sugar that may have been more readily available in the 18th and 19th centuries.

It was paired with burnt sugar from jaggery sugar and honey, tamarind ice cream, and a guava toffee.

Politics of Representation in Art.

Works of art hav the ability to freeze time. To show future generations what a glimpse of life was during a particular time. What people did, where they went, what they wore, what their ideals were, and what they ate. Just as important when examining a piece of art is to remember those who are not depicted and the meaning that can inflict on a piece. The 18th and 19th centuries in the Caribbean were a time of turbulence, growth, and change. During this time, enslaved people constantly rebelled against slavery right up until emancipation in 1834. The British slave trade officially ended in 1807, making the buying and selling of slaves from Africa illegal. However, slavery itself did not end until August of 1834 in the British Caribbean following legislation passed in 1833 (Archives, para 3). Even though slavery had ended, enslaved and indigenous people had very little upward mobility. However, a small population began to emerge in the Caribbean as members of the middle and upper class. These individuals would then become the subject of artists throughout the Caribbean.

Through a historical analysis, this project aims to examine paints by the Italian artist Agostino Brunias (c.1730-96) and the French artist Marius-Pierre Le Masurier (active 1769-75) to explore the interactions between different races, particularly minorities, in the Caribbean during the 18th centuries via their interactions with agriculture and food. By examining agriculture, the manufacturing of the commodities, those individuals who are depicted as well as those who are not, and how these individuals interact with each other to shed light on the different food inequalities that groups of people experienced during the 18th and 19th centuries.

During my research, I came across a Content Creator at Art UK named Lydia Figes, who states that even though the painting is “aesthetically pleasing, yet not without political intent, Brunias' paintings served as a form of propaganda. Promoting Young's imperialist mission, he promoted the West Indies as a 'thriving colonial economy'’ a place of opportunity where the generations of deported African peoples were not resisting their enslavement. Rather than presenting an objective reality – he painted in the tradition of 'vérité éthnographique' (meaning 'ethnographic truth') – his works omitted the violent realities, punishment, and discipline of enslaved labor. Instead, Brunias captured diverse and joyous social gatherings of slaves, freed people of color and colonizers, mirroring images of the refinement and respectability found in Europe.”

By examining the painting by Brunias and Le Masurier, I draw comparisons in the foodway systems between those of European descent compared to freed people of color, freed people of color compared to enslaved people, and enslaved people compared to indigenous people. Then I examine how these paintings and their hidden messages of colorism and racism are connected to the American Supermarket, specifically with the “ethnic” aisle. People of color have been fetishized due to an obsession with “exoticism” through the food they prepare and consume. Even today, there is still a clear sense of “otherness” that non-European and American cuisines face. But before we can examine depictions of food stereotypes of today, we must first examine the past.

Analysis of Agostino Brunias, The Barbados Mulatto Girl, 1779.

Agostino Brunias was an Italian painter during the 18th century in the Caribbean. He started painting various planter families and their plantations in the West Indies and scenes featuring free people of color and cultural life in the West Indies (Tate, para 1). Historians have praised his subversive depiction of West Indian culture, while others claimed it romanticized the harshness of plantation life (Tate, para 1). Within this paper, I aim to examine how his ethnicity and class status and the second artist, Marius-Pierre Le Masurier, affected the way he depicted the subjects within his paintings. The first painting I will be examining is Agostino Brunias’s The Barbados Mulatto Girl from 1779 (fig. 1).

It is important to note that the sexual relationships between the white planter population and the African slaves created a mixed-race community of free people known as gens de couleur or ‘people of color.’ As they were descendants of relations between white planters and Africans, members of this group rose to become wealthy members of colonial society and even owned slaves. However, this community of people faced barriers due to colorism (Smith, para 6). One area that I believe academia needs to conduct research on is the psychological effects this community had experienced in owning slaves but not being a part of the white colonizing society. It must have been difficult for this community to own slaves and to see them treat people similar to them in a particular manner to maintain a specific class image. What were the relationships like between the cook and the woman of the house? Did they have a similar palate? Did cooks have more freedom for personal expression and creativity? On the reverse side, did the ‘people of color’ have eating disorders to adhere to what was considered ideal body figure-wise (Gordon, para 1)?

Here there are three colored individuals, two dark-skinned that are off to the side. In the center of the painting, a lighter skin toned woman dressed more elaborately than her two counterparts. Both darker-skinned individuals appear to be women and have a lower economic standing than the central figure. The dark-skinned individual who stands on the viewer’s left-hand side is dressed only from the waist down in a red skirt, with another piece of fabric tucked in blue and white stripes. She wears a headscarf that is the same red color as her skirt, but with white checkerboards, and then on top of that, her face is wrapped in a piece of white fabric wrapped around her neck and tied in a knot on the top of her head. In her hand, she holds a small basket filled with yellow fruit. The center figure looks at this individual though her body faces the other dark-skinned individual.

To the viewer’s lower right-hand side, another woman is depicted. She, like the woman to the left, is dark-skinned. Instead of standing, she sits on an upside basket. Her right leg is stretched out, while her left is bent. She is fully dressed, wearing a white top and predominantly white skirt with blue stripes. She also hears a head wrap, though hers is white. Her left elbow sits on her left knee as she gestures to one of the yellow fruits or vegetables she holds towards the central figure.

The center figure is lavishly dressed. She wears a yellow underskirt, with a white dress on top, with a corseted top that is red and white. She has a large star necklace with pearls and bracelets, and her head wrap extends up into the air. She appears to be pregnant or well feed. Weight was a sign of wealth, as it meant an individual was well fed, it indicates her class status. Her left-hand lifts up the corner of her white dress so it folds over while her right hand extends toward the fruit or vegetable that the woman in the right is gesturing toward her. She has a slight smile toward the woman on the left.

Brunias emphasized the central figure as she is what is known as a "mulatto” or mixed ethnicity individual. Though she is the central figure in this painting, Brunias did not provide her name. She is also referred to as a girl, compared to a woman. A subtle hint to the idea that she is less than her white female peers as she is not provided with a name and is only identified with the noun child. Children may have less respect bestowed upon them than an adult thus degrading her status. She is an anonymous free woman of color purchasing fruit and or vegetables from enslaved vendors (Free, para 1). Here we have a depiction of how freed women of color may have attempted to help the status of specifically enslaved women by providing them with a source of income. The source of income could have potentially allowed them to buy their freedom. The mulatto woman's right hand is stretched similarly to God's hand in Michelangelo's The Creation of Adam in the Sistine Chapel. This could be Brunias's way of hinting that the mulatto woman provides a livelihood for her enslaved counterparts.

Furthermore, the scenery and the fruit or vegetable are just as important as the individuals. The three women are placed on a road or path that has been cleared of any vegetation, while around them, the landscape is green and lush. In the far background, a building has white walls and a blue roof surrounded by a few palm trees. The landscape is lush and green, a symbol of prosperity, and yellow symbolizes happiness and optimism, enlightenment and creativity. By depicting a lush environment, both the land with its thriving vegetation and the women whose voluptuous bodies exude a sense of organic sensuality. Coincidentally, the same descriptors are frequently applied by eighteenth-century European travelers to convey the natural wonders of the Caribbean – words such as ‘lush’ and ‘torrid’ often carry the possibility of a naughtier connotation; ‘succulent flesh’ might just as easily describe the body of a woman as the meat of a coconut (Bagneris, 136).

Analysis of Marius-Pierre Le Masurier, Marché à Saint Pierre de la Martinique, 1775.

The painting Marché à Saint Pierre de la Martinique by Marius-Pierre Le Masurier depicts what the indigenous women and children may have encountered once they reached the marketplace. Le Masurier depicts people of different colors, races, gender, social status, and economic status interacting with one another. It is important to note that the artists tried to create an idealized environment in many pieces of artwork. Therefore, the viewer should remain skeptical while viewing art.

In the foreground, the flourishing marketplace is located next to the harbor. Boats are depicted in the middle ground. In contrast, the untamed wilderness is in the far background. The marketplace is located next to the coastline representing prosperity and life, as water provides life. Le Masurier has separated the paintings into groupings of people, each with their fascinating interactions.

The details sections of the painting depict images of an indigenous naked boy paired with “exotic” animals such as birds and a monkey trying to sway a European couple to possibly purchase one of the animals or pay him for providing some form of entertainment. The European couple has brought their servants along as a dark-skinned woman is carrying a box with folded fabric on top. The European man addresses the indigenous boy while the European woman looks forward at a female African merchant who is presenting a blue-ish gray fabric towards the couple. Once again, the artist has used clothing to distinguish between the indigenous and those brought from Africa who have been “civilized” and introduced to society. Thus, creating tension between Africans and indigenous people. Those who have been “enlightened” by society are dressed in white, a symbol of purity, while those who have not been “exoticized” by the lack of clothing and the additional element of animals. The monkey remains close to the indigenous boy, reminiscent of how a toddler would remain near their mother. Le Masurier could be hinting at the racism that indigenous people encountered as they could have been thought of as animals and less than human.

Slightly underneath the European couple interacting with the indigenous boy and the female African merchant, I focus on Figure 7. We see an interaction between a light-skinned African woman smiling and a white male with one arm around her shoulder. Both individuals appear to be smiling at one another, and the viewer may infer that a more scandalous encounter could be happening between the two of them. This seems to be a rare encounter between sexes as this time period had strict rules regarding how genders could interact. The woman wears a white top but has a light blue and white striped skirt with a red scarf around her shoulder and a red hair wrap. This detail is not to be ignored as her scarf and head wrap signify class status. The freed people of color are women and men, born free or freed, black or mixed race, who were legally free, but who were nevertheless discriminated against, notably because of the color of their skin and their racial and ethnic origins. This socially and legally discriminatory system, which was introduced in colonial society during the 18th century, is called prejudice of color (Pierre-Louis, para 1). Strict regulations were made in clothing to distinguish free people of color compared to enslaved people who worked in the field and those who worked in the house (Pierre-Louis, para 3).

The placement and color of her scarf draw the viewer's attention to her chest, which the man is leaning into, thus furthering the idea of interracial sexual relationships. The man appears to be of a lower-class status than his other white male counterparts as he does wear the powdered white wig. His shirt is also slightly unbuttoned as the viewer can see a sliver of his chest. His European male counterparts are completely covered, and the only skin that is shown for them are their faces and their hands.

Figures 4 an 5 focuses on the bounty of commodities available in this market. Bananas, eggs, artichokes, papayas, lychee, mangos, peppers, and melons. In addition, there is a sea turtle, fish, and a basket of birds, possibly pheasants. Le Masurier uses bolder and brighter colors when depicting the produce and animal life native to the island compared to the inhabitants. At Sunday markets, enslaved peoples bought, traded, and sold the produce of their provision grounds, modest plots of land allotted to them for small-scale agricultural pursuits, and the raising of livestock and products that they had made or purchased (Bagneris, 94). These parcels were not gifts from their enslavers to the black men and women, as enslaved people were considered property. These provision grounds served alternative interests of the planters as these lands supplemented the rations provided for enslaved families on most islands or fed them almost entirely in others (Bagneris, 94).

Here the adults depicted are dressed less formally than their counterparts previously mentioned, and the children are naked, thus indicating that they are of a lower social class. The seated woman has her shoulders exposed, and her dress appears to be ill-fitting. The man wears white pants with a blue shirt that is undone. The man reaches out to the woman and has his hand under her chin lovingly and concernedly. The look on their faces depicts sorrow and a life of struggle. The two children are clinging to their mother, and one of them is hungry as the woman breaks off a piece of melon to feed them.

In addition, Le Masurier has placed them in a bubble within the painting, thus alluding to the idea that they have very limited contact with people outside of the social class. Even though they are in the center of the painting, they are isolated as they do not have any customers. Le Masurier has also depicted them as dark-skinned individuals. While Le Masurier may not have intended this to be an interpretation, a modern viewer may analyze this as a subtle nod to the fact that people of African descent have had a significant role in building the modern-day economy of the Caribbean while being considered outsiders. Here Le Masurier could be alluding to colorism and prejudice among people of color. While light-skinned women can have interactions with others, this family seems to be ignored by the community.

My Modern Interpretation of Their Artwork

Title: Diaspora

Size: 36’’x 48’’

Materials: Paper, Paint, Hot Glue, Black Rhinestones, Gold Leaf, Canvas.

The art piece below is the artwork I created while creating a tasting menu based on works of art by the Italian-English painter Agostino Brunias, who emigrated to Dominica, and the French painter, Le Masurier, who emigrated to Martinique.

These two painters were instrumental in understanding, classifying, and ranking human beings according to their skin color. The tools utilized by these painters encompassing art history, science history, and political history, are indispensable in the historical investigations regarding race. Their ideal of landscapes and interactions among individuals of different ethnicities and social spheres attempted to counteract the brutality of reality.

The artwork I created is my interpretation of their works of art. The patterns created by the paper are meant to be an interpretation of Impressionism, a style of painting that these artists may have been influenced by. The colors are taken directly from their works as they used a greenish-blue-black and pops of a copper-like color. The division between the two sections is meant to represent the division among people, and the cavernous area represents the population of people who fall between two worlds and will never be able to fully integrate into one population.

The Process:

I created this piece of art by painting one side of the paper black and the other a dark green, blue, and black color. Then I would cut the paper into stripes and then roll or quill the pieces of paper into a cone shape. The cones ranged in size, length, and color. After a substantial amount of cones had been created, I started to glue them to a canvas that I painted a copper color. During the gluing process, I let the paper dictate the patterns and shapes that were created; however, I knew I wanted two separate sections of the paper forms on the canvas.

Once I had all the paper attached to the canvas in a form I was happy with, I had to tackle the blank center area. I originally was going to incorporate words relating to the recipes I created or the food depicted in the paintings, but then I decided to create more dimension within the painting and add slightly more color. I landed on the idea of including black rhinestones in that area. I utilized two types of black rhinestones, which appear more purple against the copper.

At the very end, I decided to add gold leaf to the end of certain cones for an extra layer of dimension.

In total, 110 hours and 30 minutes were spent physically creating this piece.

References

Archives, The National. “Caribbean Histories Revealed.” The National Archives, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey TW9 4DU, 10 Nov. 2006, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/caribbeanhistory/slavery-negotiating-freedom.htm#:~:text=Most%20spectacular%20were%20the%20slave,Jamaica%20led%20by%20Sam%20Sharpe.

Bagneris, Mia L. Colouring the Caribbean: Race and the Art of Agostino Brunias. : Manchester University Press, 24. University Press Scholarship Online. Date Accessed 23 Feb. 2022 <https://www.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.7228/manchester/97815261204 58.001.0001/upso-9781526120458>.

Bagneris, Mia L. "Can you find the white woman in this picture?". Colouring the Caribbean. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 2017. < https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526120465.00009>. Web. 1 Apr. 2023.

BELL, David & Gill Valentine, 1997. Consuming Geographies: We Are Where We Eat. London: Routledg

Bindman, David. "Representing Race in the Eighteenth-Century Caribbean: Brunias in Dominica and St Vincent." Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 51 no. 1, 2017, p. 1-21. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/ecs.2017.0044.

Figes, Lydia. “Agostino Brunias and Depicting People of Colour in the Colonial Caribbean.” Agostino Brunias and Depicting People of Colour in the Colonial Caribbean | Art UK, 25 July 2019, https://artuk.org/discover/stories/agostino-brunias-and-depicting-people-of-colour-in-the-colonial-caribbean.

"Free Woman of Color, Barbados, late 1770s", Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed April 15, 2022, http://slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/766

Galarza, G. Daniela. “Perspective | Stop Calling Food 'Exotic'.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 8 July 2021, www.washingtonpost.com/food/2021/07/07/exotic-food-xenophobia-racism/.

Gates, Jr. and Alejandro de la Fuente, of The Image of the Black in Latin America and the Caribbean, due for publication in 2019, which is to be a companion to the series The Image of the Black in Western Art.

Gordon, Kathryn H, et al. The Impact of Racial Stereotypes on Eating Disorder Recognition. Department of Psychology, Florida State University, 19 July 2001, www.stat.berkeley.edu/~hhuang/STAT152/Impact-of-Racial-Stereotypes.pdf.

Krishna, Priya. “Why Do American Grocery Stores Still Have an Ethnic Aisle?” The New York Times, The New York Times, 10 Aug. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/08/10/dining/american-grocery-stores-ethnic-aisle.html.

Levitt, Aimee. “A Tasting-Menu Restaurant Transforms Itself into a Multimedia Art Gallery.” Eater Chicago, Eater Chicago, 18 Jan. 2022, https://chicago.eater.com/2022/1/18/22889698/esme-paul-octavious-tasting-menu-gallery-jenner-tomaska-katrina-bravo.

Pierre-Louis, par Jessica. “The Repeal of the Prejudice of Colour in the 1830s.” Tan Listwa, 7 Jan. 2021, tanlistwa.com/2020/02/25/the-repeal-of-the-prejudice-of-colour-in-the-1830s/.

Shamo, Lauren. “Is the Ethnic Food Aisle Racist?” Business Insider, Business Insider, 30 Oct. 2020, www.businessinsider.com/hidden-racism-in-your-supermarkets-ethnic-food-aisle-2020-10.

Smith, Blake. “On Prejudice; An 18th-Century Creole Slaveholder Invented the Idea of ‘Racial Prejudice’ to Defend Diversity among a Slaveowning Elite.” Edited by Sam Haselby, Aeon, Aeon Magazine, 4 June 2022, aeon.co/essays/what-if-prejudice-isnt-what-causes-racism.

Tate. “Agostino Brunias C.1730–1796.” Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/agostino-brunias-3824.

Thomas, Sarah & Eaton, Natasha (2022) Swollen detail, or what a vessel might give: Agostino Brunias and the visual and material culture of colonial Dominica, Atlantic Studies, 19:1, 60-85, DOI: 10.1080/14788810.2021.1930773